The Vietnam War and Performance Measurement

By NRC on October 12, 2017

-By Tom Miller-

A self-confessed "stats guy," Tom Miller examines the consequences of Robert NcNamara's use of performance metrics to support policy decisions.

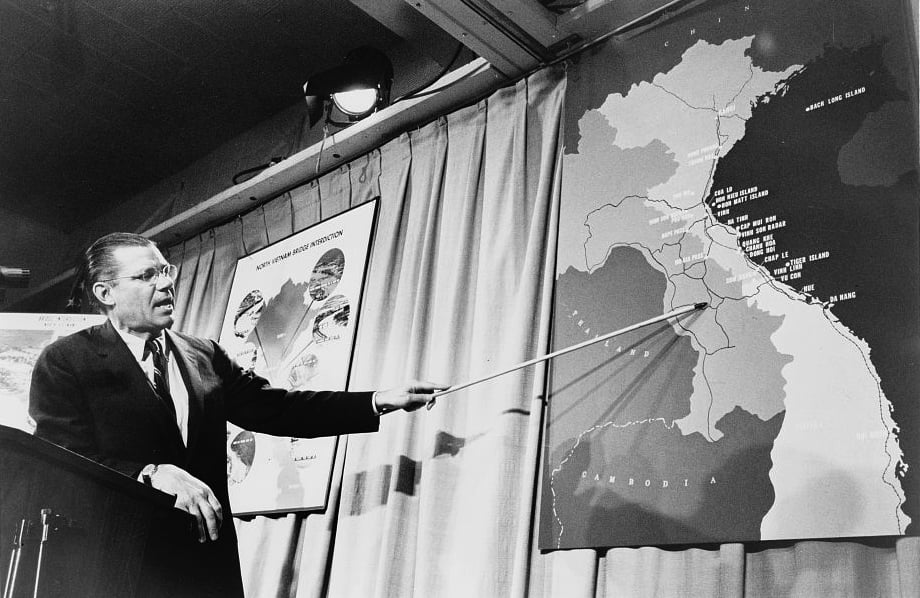

As I was watching the new series The Vietnam War from PBS, I found myself fascinated by Robert McNamara’s penchant for performance metrics, which he brought from the Ford Motor Company to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ defense department. Extolled—and derided—as a “human computer,” McNamara had earned a reputation as an expert at measuring corporate and government processes to improve efficiencies.

In local government, we too have a deep interest in measuring performance, using hard data to tell our stories of success and challenge. While the Vietnam series is a documentary about the motivations and waging of that war, it also is a history lesson about how we make policy decisions.

Like McNamara, at least in this small way, I am a stats guy. Data-based decisions are better, in my thinking, than are decisions that come only from the gut and the knee. I know I’m not a “whiz kid” or one of the “best and the brightest,” but I resist the shibboleths that proclaim statistics the enemy of common sense. Yes, you can lie with statistics, but you can lie even better with words.

My bow to numbers made, it also is clear to me that performance data alone or the wrong performance data can misdirect vital policy conclusions. A quote from USAID’s Rufus Phillips in Episode 2 of the Vietnam series offers a relevant illustration and a caution to all of us in the performance measuring business:

“Secretary McNamara decided that he would draw up some kind of chart to determine whether we were winning or not and he was putting in things like numbers of weapons recovered, numbers of Vietcong killed . . . very statistical. And he asked Edward Lansdale who was then in the Pentagon as head of special operations to come down and look at this and so Lansdale did and he said, ‘There’s something missing.’ And McNamara said, ‘What?' and Lansdale said, ‘The feelings of the Vietnamese people.’ You couldn’t reduce it to a statistic.”

The PBS series is filled with implied criticism of the exclusive use of numbers to draw conclusions about the success of the war (and separately, it vilifies the lack of transparency from the government and military).

Like the war efforts of mid-Twentieth-Century America, local governments that work the front lines of performance management these days are intent to measure what matters, but unlike the federal government of the last millennium, today’s jurisdictions toil to be fully forthcoming with their findings.

Yet it also is true that for modern-day jurisdictions, secondary data alone that inform the status of processes (potholes filled, park acreage) or the proxy outcomes of government interventions (travel time across town, numbers of crimes) are likely to miss the fundamental point of government policy decisions. We need to understand what the people think of their lives and community. And the best way to know what the people think is to ask them.

This article originally appeared on ICMA.org.

Featured Image: Robert McNamara_Library of Congress_Public Domain

Related Articles

Popular posts

Sign-up for Updates

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

Top Takeaways from CCCMA’s 2017 Winter Conference

What We Learned Hosting Our First Post-COVID Virtual Conference