Data You Can’t Trust

By NRC on October 21, 2014

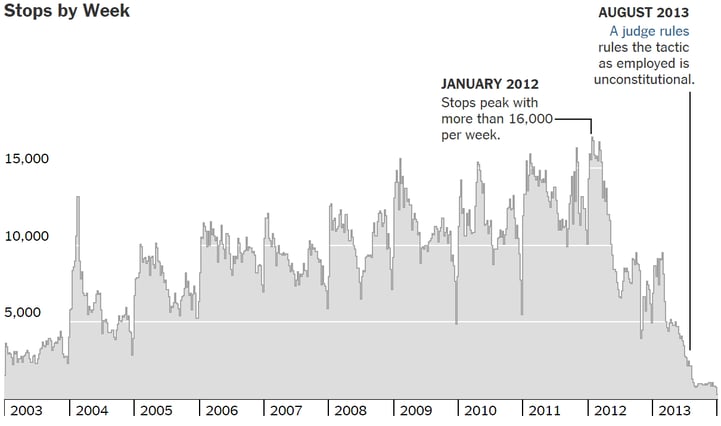

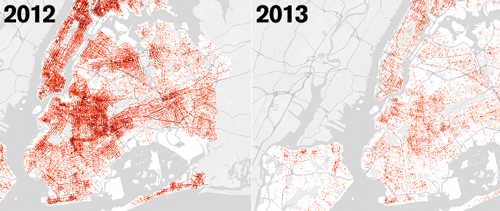

You wouldn’t think that only 34,000 stop and frisk episodes by police merited a headline about restraint. But The New York Times article, “‘Stop-and-Frisk’ Is All but Gone From New York” is all about that restraint. The report not only shows how data can tell the story of a new policy, but it also demonstrates how you may have to dig through data to reveal behaviors that undermine policy. The order of magnitude decline from 340,000 reported stops in 2012 to 34,000 in 2013 cannot be ignored and the maps in the article showing the locations of the reported stops add credibility.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s campaign ran on abhorrence of Mayor Bloomberg’s already-weakening stop and frisk policy – in part because the stops were inordinately aimed at Black New Yorkers - and with the new administration came a virtual halt to these stops.

But some have claimed that the crashing numbers of stops is nothing more than a change in name for police activities that continue. According to the Times article, Sharon Stapel, executive director of the New York City Anti-Violence Project, said, “the engagement of police with New Yorkers still allows such a high level of discretion that we can see the same tactics, they’re just not called stop-and-frisk.”

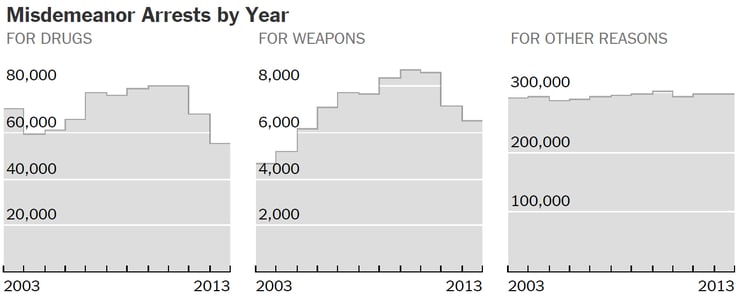

Graphs that accompany the Times article add support to Ms. Stapel’s claim. The stop and frisk policy generally netted many arrests for drug and weapon possessions, so real police restraint ought to link to a real decline in those kind of arrests. Indeed there has been decline in those types of arrest but the decline began in 2012 when the Bloomberg policy of stop and frisk was at an all-time high, suggesting that something other than the stop policy was the cause of the arrest decline – such as fewer drug or weapon possessions or an inclination of police to report fewer possessions or to look for such possessions during a stop.

Figure 2: Drug and Weapons arrests fall as stops fall but remain close to levels seen in 2004 when stops were active. Source: New York Times

Figure 2: Drug and Weapons arrests fall as stops fall but remain close to levels seen in 2004 when stops were active. Source: New York Times

In fact, according to the graphs in the article, by 2013, while arrests for illegal drugs were slightly lower than they had been in 2004 when stop and frisk was actively pursued, weapon possession arrests remained higher and were even higher than in 2005 when stops were ramping up. So police have found new ways to capture folks with drugs or weapons or they continue to use the old method – stop and frisk – but call it something else. That conclusion would square with the Times’ own speculation: “many who live and work in the neighborhoods say they see scant evidence of change, and some say the police are simply not reporting some or all of their stops.”

Evidence in the Times’ article points to an answer to its own question: “Has It Really Ended?”

Answer: “No.”

Popular posts

Sign-up for Updates

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

ARPA Surveys Inform and Justify Government Spending Decisions

Media Influence and Trust In Police Among the Black Community